Fans of British comedy will recall the episode of ‘Blackadder’ in which Robbie Coltrane’s Dr. Samuel Johnson is furious to discover he has forgotten to include the word “sausage” in his dictionary of the English language. Very funny, and almost as silly as writing an art history book about trees and neglecting to mention Andrew MacCallum, but ‘Silent Witnesses: Trees in British Art, 1760-1870’ does just that.

Inevitably, there is plenty of Turner, Gainsborough, and Constable and ample attention paid to the oaks, beeches, and birches of Paul Sandby, George Price Boyce, J.W. Inchbold and even the hallucinogenic blobs of Samuel Palmer, but never once does the name of Andrew MacCallum – the most accomplished painter of woodland in the history of British Art – come up. The author is an art historian at Oxford Brookes University, for whom I have one word… “sausage!”

Andrew MacCallum was one of 19th century Britain’s most gifted and assiduous painters of pure landscapes; pictures of places rather than people, where the topography is not just scenery, it’s the star. What figures there are play a supporting role; providing scale and a little human interest.

For more than four decades Andrew MacCallum exhibited annually at the major British venues including the Royal Academy, the British Institution, the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Cambrian Academy, Liverpool Academy, the Royal Birmingham Society, the Grosvenor Gallery, the Dudley Gallery, and at the Victorian Era Exhibition in 1897. He also scored major successes internationally at the Paris Salon and the first official World’s Fair held in America in 1876, and among his famous patrons he counted Queen Victoria.

Born in Nottingham in 1821, Andrew MacCallum clearly didn’t fancy a lifetime surrounded by looms and lethal chemicals in the city’s textile industry and, intent on becoming an artist, enrolled at the newly opened Government School of Art and Design, an offshoot of the London school under the tutelage of James Astbury Hammersley. When the latter was appointed headmaster of the new Manchester school in 1849 his first act was to make his star pupil deputy. But the prodigiously talented MacCallum was as likely to content himself with teaching in Lancashire as lacemaking in the Midlands and that same year made his London exhibition debut at the British Institution and the Royal Society of British Artists.

‘Old Trent Bridge, Nottingham’ by Andrew MacCallum

‘Old Trent Bridge, Nottingham’ by Andrew MacCallum

Royal Society of British Artists Exhibition, 1849

Now available to view at our Gallery page

Academy Fine Paintings now has available three paintings by Andrew MacCallum representing his early, mid, and later career. Exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists in 1849, ‘Old Trent Bridge, Nottingham’ depicts the ancient 14th century viaduct in its final years prior to demolition in 1871.

‘Old Trent Bridge, Nottingham’ (detail)

‘Old Trent Bridge, Nottingham’ (detail)

After making his Royal Academy bow in 1850, MacCallum moved to London to become a stipendiary student at the future Royal College of Art under its newly appointed superintendent – the art historian, educator, and Royal Academician – Richard Redgrave. Although its initial purpose was to train competent draughtsmen for Britain’s manufacturing industries, under Redgrave’s innovative methods of teaching the nascent RCA was beginning to rival the Royal Academy Schools as the country’s foremost fine art training college.

Whenever the 19th century preoccupation with “truth to nature” – the artistic doctrine emphasizing the importance of accuracy and direct observation when depicting the natural world – is discussed these days it is always in relation to the philosophical and spiritual theories of John Ruskin. However, Redgrave was a proponent of this same dictum and his unpretentious and pragmatic approach to teaching made a lasting impression upon the young Andrew MacCallum. During a sketching tour to North Wales in 1853 he wrote to Redgrave back in London assuring him that “acting upon his advice” he had “gone to nature with singleness of heart”, echoing both Redgrave’s practice and Ruskin’s theory.

In a famous passage from the first volume of his seminal work ‘Modern Painters’ Ruskin recommends that, when painting a landscape, young artists should “go to Nature in all singleness of heart, and walk with her laboriously and trustingly, having no other thoughts but how best to penetrate her meaning, and remember her instruction.”

Put simply; paint what is actually there and make it as exacting and faithful as possible.

Contemporary wisdom would have us believe that Ruskin’s words reverberate in the painstaking detail of early Pre-Raphaelite paintings, but in fact – with their lurid colours, false perspective, and artificial lighting – they really do not, as the rest of his advice to young landscape painters, taken from the same paragraph, demonstrates.

According to Ruskin: “Nothing is so bad a symptom in the work of young artists as too much dexterity of handling; for it is a sign that they are satisfied with their work and have tried to do nothing more than they were able to do”. But if John Ruskin believed young artists should “keep to quiet colours: greys and browns” and eliminate “their crude ideas of composition” then he can only have found his landscape doctrine contradicted in every gaudy green blade of PRB bocage.

Although Redgrave and Ruskin shared a passion for nature, their concepts of “truth” were quite at odds. As Redgrave pointed out in ‘A Century of Painters of the British School’ published in 1890, Ruskin’s opinions are inconsistent and contradictory, never more so than in his attempt to reclassify JMW Turner as “the first and greatest of the Pre-Raphaelites” who stood for everything the former would have found fatuous. Where Ruskin saw evidence of the PRBs “one principle; the uncompromising truth of working everything from nature and from nature only” in the work of Turner – who repudiated topographic imitation, idealized the everyday, and selected only the sublimely beautiful in nature – is anyone’s guess. If Turner and the Pre-Raphs shared anything in common it was a marked disinterest in the Literal. On the other hand, if any artist of the period exemplified the “selecting nothing, rejecting nothing” tenet of Ruskinian theory it was Andrew MacCallum.

Our second painting by Andrew MacCallum (available shortly) is ‘The Oaks of Cranbourne Chase, Windsor Great Park’, depicting the ancient trees of the royal forest with a family of deer basking in the winter sun. It was exhibited in London at the Royal Academy in 1863.

‘The Oaks of Cranbourne Chase, Windsor Great Park’ by Andrew MacCallum

‘The Oaks of Cranbourne Chase, Windsor Great Park’ by Andrew MacCallum

Royal Academy Exhibition, 1863

Coming soon to our Gallery page

As a student of what became known as “the South Kensington System” Andrew MacCallum’s exacting art education was also guided by the school’s other eminent tutors – John Callcott Horsley and, in particular, John Rogers Herbert. A follower of the German Nazarene movement (and an enthusiastic Catholic convert) Herbert was a painter of Biblical and Medieval scenes that, in both style and execution, were a major inspiration to the decade’s most famous art movement, the aforementioned Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. One of the stated intentions of the PRB was to “out Herbert, Herbert”. However, whilst over at the Royal Academy Schools the young John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt were doing their best to emulate the art of Herbert, a five-minute stroll up the Strand, Andrew MacCallum was being taught by the man himself.

‘The Oaks of Cranbourne Chase, Windsor Great Park’ (detail)

‘The Oaks of Cranbourne Chase, Windsor Great Park’ (detail)

The high esteem in which the young MacCallum was held by Redgrave and Herbert was formally recognised when he was awarded a travelling scholarship to Italy. Journeying alone across Europe in 1854 was not the short, safe, and simple jaunt it is today, but then Andrew MacCallum was never a man to shy away from a challenge. His mission was to execute meticulous copies of the frescoes, altarpieces, and murals in Italy’s famous churches and galleries, but it would also afford him time to concentrate on his own work.

After arriving first in Milan to copy Leonardo’s mural of ‘The Last Supper’ at the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the paintings of Bellini and Titian in the Pinacoteca di Brera, he moved on to Verona, Florence, Mantua, and Venice to draw facsimiles of the frescoes and altarpieces of Mantegna, Tintoretto, and Veronese etc. before finally arriving in Rome to record the works of Raphael in the Vatican. Whilst there he was also able to sketch the ancient ruins of the Forum and venture out of the city to make preparatory drawings of the Campagna that later formed the basis for epic exhibition paintings back in England.

‘Rome: Sunset over the Temple of Concord and the Forum’ by Andrew MacCallum

‘Rome: Sunset over the Temple of Concord and the Forum’ by Andrew MacCallum

Image courtesy of Abbott & Holder, London

Throughout his time in Italy Andrew MacCallum sent his illustrations back to London where they were exhibited at the newly formed Victoria and Albert Museum. Today, almost 170 years later, the original manuscript of MacCallum’s ‘Report of a Sojourn in Italy from the year 1854 to 1857’ is preserved in the V&A library.

On arriving back in London the artist was obliged to fulfil his commission by decorating the exterior of the museum’s new Sheepshanks Gallery, a considerable undertaking but a very appropriate one. Having spent the past three years studying the lavish civic commissions of the Italian Masters, who better to decorate the new Italianate façade of the Victorian & Albert Museum. The ornamental brickwork was designed in the Northern Renaissance style, with arched Paladian windows and double-height Florentine pilasters, incorporating MacCallum’s sgraffito-work.

In the photograph below, Andrew MacCallum can be seen standing in front of the new gallery with work still under construction, and at its opening in 1857 with Richard Redgrave and and his Royal Highness Prince Albert (left).

In its 1877 article dedicated to the life and career of Andrew MacCallum ‘The Art Journal’ reserved special praise for the artist’s enormous skill at painting trees. Certainly, it was MacCallum’s highly detailed depiction of everything from English oaks and beeches to the exotic palms and Cypress trees of the Mediterranean that made his reputation, not only in London but also in Paris with a group of artists who would inspire one of the most famous art movements in history: Impressionism.

‘Autumn Sunlight after Rain, Fontainebleau’ by Andrew MacCallum

‘Autumn Sunlight after Rain, Fontainebleau’ by Andrew MacCallum

Image courtesy of the National Museums & Galleries of Wales

Living and working around the Forest of Fontainebleau to the south of Paris, the painters of the Barbizon School – Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny etc. – are widely (albeit incorrectly) credited as the first landscape artists to paint outdoors. Although they certainly sketched en plein air they did no actual painting there. During the winter of 1861 the only artist to be found in the forest with oils and an easel was Andrew MacCallum, and in the most inclement weather. This practice earned him the nickname “Le Diable Anglais” among the Barbizon painters, but their astonishment was accompanied by obvious admiration.

It is no surprise then that MacCallum received such approbation when making his debut at the Paris Salon in 1862. When his large Fontainebleau landscape ‘The Vanguard of the Forest’ was exhibited at the Académie des Beaux-Arts it was so admired by his peers that one of the French Academicians withdrew his own picture from its prestigious place “on the line” (at eye level) so that MacCallum’s painting might be given pride of place. An extraordinary gesture it is hard to imagine replicated back at the Royal Academy, or at any other venue for that matter.

In 1866 a one-man exhibition of MacCallum’s work at the Dudley Gallery in Piccadilly featured several of his Fontainebleau paintings alongside others of Sherwood Forest and Burnham Beeches. According to one reviewer, “The giants of the forest were never celebrated by a hand more faithful and laborious.”

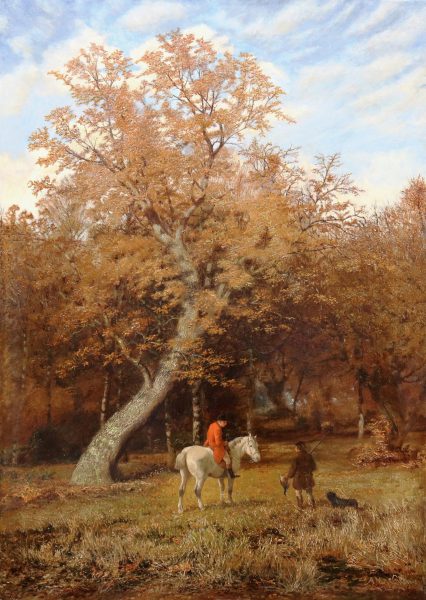

‘A Scion of a Noble’ by Andrew MacCallum (1889)

‘A Scion of a Noble’ by Andrew MacCallum (1889)

Grosvenor Gallery Exhibition, 1889

Now available to view and purchase at our Gallery page

Our third painting by MacCallum was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in London in 1889. Ostensibly, the title refers to the aristocratic young gentleman in hunting pinks on horseback talking with his gamekeeper, but of course it also alludes to the leaning beech tree towering above him which, for MacCallum, is also the offspring of a noble line. We are left wondering if the young lord is, in his own way, as crooked and shady as the tree.

In 1871 Andrew MacCallum’s constant search for new challenges and exciting places to paint saw him set a course for North Africa to take on the great Orientalist subject that would become the focus of his mature career; the River Nile and the sites of Ancient Egypt.

British artists had been travelling to North Africa since the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but the spectacular desert landscapes of William James Müller, Frederick Goodall, and Frank Dillon were now at the peak of their popularity. Naturally, most people could not afford to buy the paintings themselves but the secondary market for the lithographic prints was brisk. Epic, exotic and affordable they offered ordinary people a glimpse of a mysterious and magnificent world they would never see for themselves.

MacCallum’s first trip to Cairo also took in the Great Pyramid and Sphinx at Giza and sufficiently whetted his appetite that he made three further visits to Egypt; each one venturing further up river to the tombs of Beni Hasan, into the Western Sahara to Dendera, Karnak, and the Valley of the Kings at Thebes, and finally in 1874 on to the island of Philea, site of the great temples of Isis and Trajan.

‘Temples at Philae on the Nile’ by Andrew MacCallum (1874)

‘Temples at Philae on the Nile’ by Andrew MacCallum (1874)

Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, London

During this last expedition MacCallum joined the travelling party of the English Egyptologist Amelia Edwards, a journey recounted in the celebrated Victorian travel book ‘A Thousand Miles Up the Nile.’ During his time spent with Edwards and her party “The Painter”, as she called him, extricated his ladies from difficulty on more than one occasion, and at Abu Simbel the intrepid MacCallum even discovered a three-thousand-year-old chamber near the ancient rock temples of Pharaoh Rameses II.

His deliberately circuitous return journey to England in 1875 involved stays in Jerusalem to sketch the famous sites of what was then still known as “the Holy Land”, in Constantinople (Istanbul), and in Athens where he conceived an epic canvas of ‘The Plains of Marathon’ and another of the Acropolis that was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1876.

‘The Plains of Marathon’ by Andrew MacCallum (1874)

‘The Plains of Marathon’ by Andrew MacCallum (1874)

Image courtesy of the Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece

Later that year Andrew MacCallum received the most prestigious commission of his career when he was invited to Scotland by Queen Victoria to paint five views of the Royal Estate around Balmoral.

His success enabled him to keep a home and studio in Kensington at the heart of London’s artistic community where his neighbours included Sir Frederic Leighton PRA, Val Prinsep RA, and his friend and fellow Orientalist landscape painter Frank Dillon. When the latter organised the ‘Exhibition of Japanese & Chinese Works of Art’ in 1878 he invited MacCallum to contribute items of antique porcelain from his personal collection.

Andrew MacCallum continued to show his work at the major London venues until 1889, spending the final decade of his life in virtual retirement. The hundreds of pictures he exhibited during his 43-year career, some of which can be found today in Tate Britian and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, are a lasting testament to his meticulous and honest brand of landscape painting. Whether for his paintings of the woodlands of England, the forests of France, the ruins of Rome, the hills of Athens or the ancient Egyptian sites of the River Nile, Andrew MacCallum should be remembered as a gifted and faithful chronicler of the natural world and the architectural achievements of its ancient peoples.

by Gavin Claxton

© Academy Fine Paintings 2025

Additional images courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sansom & Co. and BBC Television.